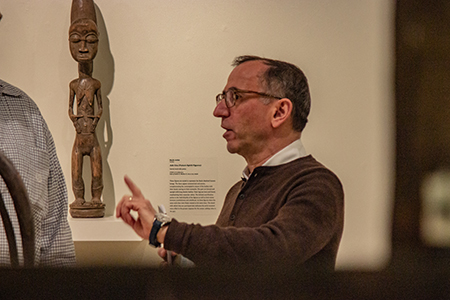

Nick Mirzoeff delivered a fascinating lecture at UW-Milwaukee on March 29 as part of C21’s spring 2019 lecture series. As a visual culture theorist/activist and a professor of media, culture, and communication, he elaborately discussed how whiteness as an ideology and white supremacy have been able to reproduce and revive themselves, despite the long period in which multiculturalism or diversity and antiracism have been widely and actively discussed in our society. His talk took its direction from what Frantz Fanon called the colonial “world of statues,” the physical presence of the statues and colonial refusal to allow mobility as “part of a global infrastructure of white supremacy and part of the production of segregated urban spaces.”

During this talk, Mirzoeff highlighted the connections between a series of contemporary crises and movements: the 2017 white supremacist march in Charlottesville, the Millions March as part of the Black Lives Matter Movement in New York in 2014, and a series of decolonizing moves against statutes, such as the Rhodes Must Fall protest movement and the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville in 2015. He talked about how museums such as the American Museum of Natural History, monuments, and formal spaces of incarceration such as a Danish refugee camp interact to sustain regimes of segregation. Historically, there has been an intersection between all of these, the crisis of power and white supremacy.

Because of this legacy, as Mirzoeff discussed, a new racial infrastructure is required in which the concept of appearance is an important matter. But what would it mean to appear? Does it mean “claiming the right to exist, to possess one’s body?” According to Mirzoeff, “To appear is to become visible or noticeable.” What can be learned from the historic unequal appearance of people of color throughout history?

Talking about the Rhodes Must Fall movement and the act of South African social and political activist, Chumani Maxwele, who carried a container of human waste from his township of Khayelitsha to the University of Cape Town and poured it over the statue of Cecil John Rhodes, Mirzoeff argues that these activists wanted “to bring another world of dispossessed into or onto the world of statues.” He explained another act of South African visual artist, Zanole Muholi, who made self-portraits while she was traveling out of Africa, as visual activism, “claiming the right to look and therefore the right to be seen.”

During the talk, Mirzoeff presented a well detailed historical narrative of the origins of the so-called infrastructural whiteness. At today’s cultural, political, and historical moment, we have witnessed a revival of the old supremacist ideas. Considering Fanon’s “The World of Statues” and the distinctions between the terms good versus evil, free versus slave, citizen versus migrant, some of these hierarchies have been even more visibly implemented, enforced by the use of scanners, facial recognition technologies, and other forms of optical equipment that surveil migrants, refugees, and people of color. Referring to Fanon and Tosquelles’s ideas, Mirzoeff argues that “whiteness is the statue, a singular self produced by segregation within the optical space of the appearance.”

The white supremacy is not just supported by the physical monuments; it was supported by other things, including art museums and books that outlined eugenicist ideology. Mirzoeff talked about the hierarchy of the human established in the wake of the Haitian Revolution (1804). We know such hierarchy through visual forms. Nott and Gilddon’s Types of Man (1859) was presented as the origins of racial types, and UPenn’s museum Morton skull collection and Madison Grant’s 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Racerepresented the idea of replacement, “the idea that there is a thread to the elite minoritarian, white ideal that became part of the general popular culture during the first World War in US.”

Considering whiteness as an infrastructure supported by institutions and expressed by structures, Mirzoeff talked about the role of New York’s American Museum of Natural History, where the 2ndInternational Eugenics Conference was held in 1921, in powering the racialized hierarchy, even within the ideology of whiteness itself, by “presenting Nordic whiteness as superior to other whites.” The Theodore Roosevelt statue outside the Natural History Museum was another example discussed in the lecture with a colonial ideology behind it. Due to the long-lasting debate over its removal, the NYC Monuments Commission reviewed the sculpture and reported that it “was meant to represent Roosevelt’s belief in the unity of the races.” Mirzoeff analyzed it based on the understood racial hierarchy of the day, however, and argues that this statue visibly embodied the idea of a eugenicist racial hierarchy.

What can be learned from all of these statues and examples? As Mirzoeff argues, “the world of statues as a network of white supremacy will not be undone with one single action, winning an election, or even revolution or uprising, it is going to be about taking apart the thousands of links and nodes that constitute the network of whiteness.” He suggests taking down all the statues commemorating white supremacy. These statues are physical nodes in the network of white supremacy. They visibly display and commemorate the established order of racial hierarchy in our public spaces. They need to be removed from the public spaces, but, they are important part of our history and their protection and preservation should matter.

Mirzoeff gives one example of how we can take some steps forward, from his own work on an exhibition titled Decolonizing Appearance at the Center for Art on Migration Politics, Copenhagen, Denmark. He presented a series of photos showing the living conditions in this refugee camp. The refugees describe it as torture, not physical but psychological, as nothing is permitted there. They can’t put anything on the walls, they can’t cook, foods are not edible, they are isolated in a location far away from the city. The exhibit examines “what appearance is, how appearance is used to classify, separate, and rule human beings on a hierarchical scale, and how we can challenge this regime.” I found this proposal invaluable and effective in taking a stand against white supremacist ideology and changing the boundaries of the established racial hierarchies.