By Tinuola O. Oladebo and Olamilekan F. Awoniyi

Masters of Sustainable Peacebuilding (MSP), Institute of Systems Change and Peacebuilding (ISCP), University of Wisconsin Milwaukee

Introduction

The Milwaukee Food System comprises part of a larger ecosystem made up of numerous food actors in the city, yet Milwaukee’s food system is hampered by limited collaboration among these food actors. Using a systems-thinking approach, this project focuses on data collection and analysis to develop an interactive food ecosystem map to strengthen collaborative operation among the various food actors using Kumu software. Kumu is a data-visualizing software platform that organizes complex information into interactive relationship maps. The project involves the application of systems mapping through the use of Kumu to reveal the unseen limitations within Milwaukee’s food system. It informs suggested models for food equity advocates to strengthen the operation of the food actors in the city to achieve sustainability. This paper shows the process and the outcome of the asset-based research that we carried out to identify the various assets of the food actors in Milwaukee and how a collaborative effort can be encouraged to improve the state of food security and accessibility for the residents of Milwaukee. This project was carried out under the sponsorship of the Masters of Sustainable Peacebuilding (UWM), Institute of System Change and Peacebuilding (ISCP), Milwaukee Food Council, and Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program-Education (SNAPed)

Study Limitation:

Data gathering and analysis formed the foundation of this effort. This paper’s findings are constrained to the three-month project’s allotted time frame which limits the amount of data that was collected and the number of food actors that were contacted. We collected 385 raw data points from the Milwaukee Food Council’s pre-existing data set on food actors in Milwaukee, and we carried out an intensive internet search to get additional actors added to this database. A total of 36 of these identified actors responded to our survey through phone calls, emails, and in-person interactions. Furthermore, we were unable to obtain accurate data from the websites of the identified food actors due to outdated information on some of them. Despite these obstacles, the data nonetheless offered crucial information to guide Milwaukee’s food system’s policy and decision-making.

Background to the study

Studies have attributed collaborative action to be an important strategy for all food actors and stakeholders connected to food production and distribution. This brings about a reduction in cost, provides more accessibility to information, and reduces duplications and wastage, all of which enhance sustainability (dos Santos et al., 2020). In support of this, Garcia-Gonzalez and Eakin (2019) argue that “any multistakeholder initiative that aims to build the basis for change in a food system, regardless of geographic scale, requires an understanding of what is important to stakeholders, how they view the boundaries of the system, and what changes they feel are needed”. The asset map we designed with Kumu shows the connectedness of the services provided by the food actors despite their siloed operations. From this discovery, we realized how their operations could be strengthened through collaborative operation, which is currently lacking. This forms the basis for our project as it is believed that understanding different perspectives of a system helps stakeholders communicate.

A collaborative operation model improves stakeholders’ operations by allowing them to assess the problems critically, through shared perspectives that enable the development of ideas about what solutions should be and how they could be implemented. Furthermore, the study conducted by Garcia-Gonzalez and Eakin (2019) shows that many food actors may be passionately invested in their work. As a result, formal methods and procedures such as focus group meetings, which make different viewpoints accessible for exploration, may be increasingly beneficial in the actualization of collective action. However, trust becomes a crucial requirement for building this movement of long-lasting change that is guided by the awareness generated by this asset map. This signifies the need for a facilitating body that initiates a community/trust-building process, which in this case is the Milwaukee Food Council.

Result/Findings

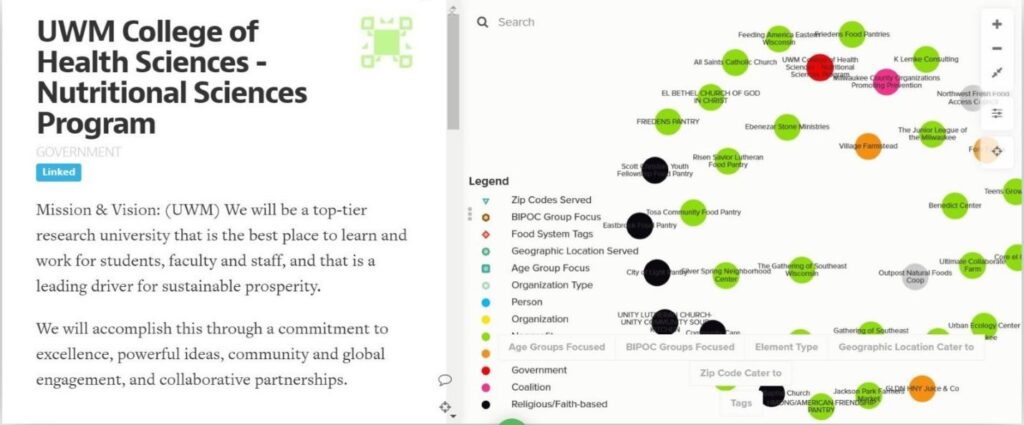

The Milwaukee Food Council has an existing food actors map that only shows the geographical location of some food actors; however, there is a need for the map to provide adequate information for the stakeholders and Milwaukee residents as shown in figure 1.

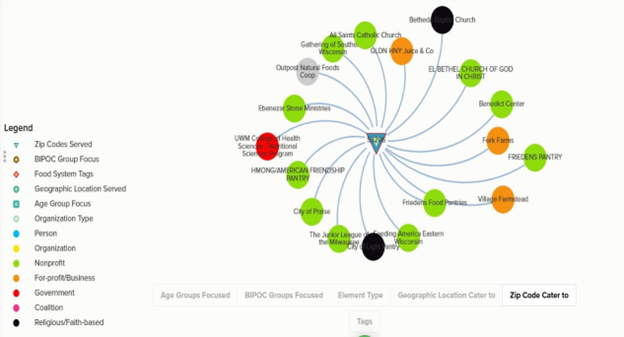

One of the discoveries in our asset map which can be found in figure 2, identifies zip code 53206, which is one of the food deserts in Milwaukee (USDA report). This zip code has at least 18 food pantries identified to be serving the community members. This shocking revelation is an example of how an individualistic operation with positive intentions does not provide a sustainable justification model to address pressing issues, which in this case is food dessert within the geographical location.

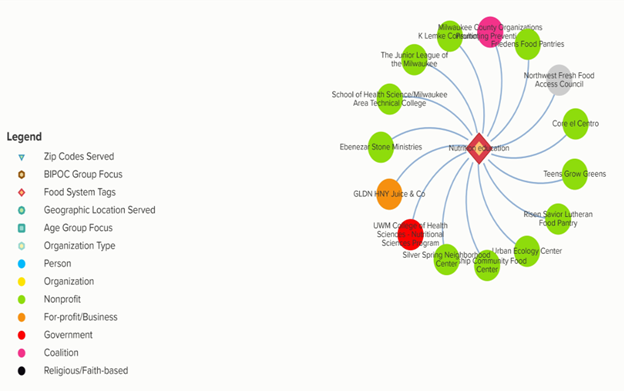

Also, through this map, we can see how siloed operations block the creativity lens of food actors to see how interconnected they all are and how their cooperative actions can provide a basis for collaborations. The image in figure 3 below provides a clear understanding of how interconnected and interrelated the different identified food actors are even when they seem to be focused on different things.

Recommendations/Conclusion

The importance of collective actions between stakeholders of the Milwaukee food system to provide shared perspectives that would help to improve Milwaukee’s food ecosystem deserves more attention. During the implementation of this project, data was gathered on location, vision, and mission, the neighborhood served, the racial group served, the services provided, and the organization/program type. The information helped us group these stakeholders in our asset map, allowing us to see overlaps in the interests and services of the mapped organizations/programs.

Although there were limitations during the execution of this project, we were able to get useful insights from the asset map as indicated in the result. After analyzing the map critically, we suggest the following actions be taken:

- Continuous data collection: The asset map was designed to automatically update itself in accordance with additional data entry, which provides the opportunity for more input on the map when additional responses are gotten from the stakeholders. Therefore, we suggest that efforts should be made towards ensuring more responses from food actors that are yet to respond to the survey form.

- Stakeholder Meeting: A meeting should be facilitated between the stakeholders that were identified on the map with the primary aim of showing them the food ecosystem asset map to show the need for collective action and inform creative suggestions on further steps for action.

- Map Publishing: The asset map should be published to inform other food stakeholders about the development to encourage their participation.

- Relationship/Community Building: Community building seminars should be organized for the stakeholders with the aim of creating the needed bond and trust building that is needed for sustainable collaboration.

Olamilekan Awoniyi is a Project Analyst and Agric Business enthusiast who owns a poultry farm in Nigeria which has helped him gain perspectives and develop his interest in the food system. He studied urban planning and gained experience as a research assistant at the Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research. He is currently a Distinguished Graduate Student Fellow (DGSF) and a second-year student in the Masters of Sustainable Peacebuilding program at UWM, where he has achieved professional experience in evaluation, facilitation, data collection and analysis, community building, and system mapping. In Milwaukee, he has worked on various projects related to community development and the food ecosystem.

Tinuola Oladebo is a developmental worker and project manager from Nigeria with over five years of experience working on various humanitarian-related projects in Nigeria and parts of Africa. She is a second-year UWM student pursuing a master’s degree in sustainable peacebuilding with a focus on maternal and infant mortality. Tinuola is also an Institute of System Change and Peacebuilding (ISCP) fellow.