By Randolph Marcum

I still remember the day my art career ended. It was during first grade, so I must have been seven years old. I was in the habit of drawing comics when I was bored. My teacher—let’s call her Mrs. Holt—was initially encouraging. The first time I brought her one of my finished creations, she said “Oh, look! Randolph drew us a comic!”, and she read it to everyone. By the fourth or fifth time that day I brought her a comic, her reaction was far more muted. “Oh, look,” she said, glancing over it briefly. “Another comic.” Looking back on it, I understand her declining enthusiasm. My art was, simply, dismal: the linework amateurish, the jokes formulaic, the main character—my cat Sassy—not nearly sassy enough. I was also drawing during math lessons, which probably didn’t help either.

This is all to say that I stopped considering myself an artist years ago. So, when I heard that Liz Kozik, a doctoral student at UW-Madison and a science communication fellow at their arboretum, was coming to C21 on November 4th for a workshop aimed at people who self-identify as non-artists as a part of C21’s Story Experience Program, I was intrigued. “I’m not an artist,” I thought to myself. “I can’t draw at all and haven’t tried to for years! This is perfect!” And so, feeling lost in the maze of my own research and writing, I wanted to try something new, or rather, to reconnect with a brief passion I had when I was younger.

When I logged in to the virtual session at 9AM (Liz herself, along with several other participants, were situated on the 9th floor in Curtin Hall), I noted first the delightful array of comics she had spread out on the table, all of them dealing with various environmental issues. In her own work, Liz studies at the crossroads of science communication, the environmental humanities, and art. Her research centers on sharing stories, through the medium of comics, about “the practices, people, and history of prairie restoration” in the American Midwest. It is this emphasis on storying and narrativizing our own work that was the focus of Liz’s presentation that day.

Near the top of the presentation, Liz made her point clear: “Anyone can draw; all you need are scribbles on the page!” What’s more, anyone can tell a story through art: “You just need to draw images in sequence.” It sounds simple, and for Liz, it really is that simple. To prove it, she used two activities. The first was a demonstration of a comic from 2008 called Milk and Moo, by Yumi Sakugawa. The comic follows two feral cats, the titular Milk and Moo, who are tasked by a dying entity to “watch over existence for me.” This leads to a sequence where the two cats see, through a series of heavily scribbled drawings, the totality of the universe: from the endless empty void that predated the big bang, to the flowering of life and the chaotic cycle of death and rebirth that marks existence. In the portion of Milk and Moo that Liz showed us, strange and evocative shapes dominate the panels; the reader can make out humans and animals and cities and crowds, but Sakugawa is careful to keep these images largely abstract. This comic, Liz insisted, is proof that the ability to draw something perfectly is secondary to the ability to imbue a drawing with expressive and narrative force.

With this in mind, Liz encouraged us to draw. Drawing is all about the manipulation of shapes to produce something recognizable, even in all its imperfection. To illustrate this, Liz had us first produce something recognizable—Batman, in this case—in ever-shortening increments of time. We often think of drawing as taking a long time, but if the goal of your drawing is teasing out a certain quality of expression—a quality, in other words, of feeling that the drawing produces—rather than perfecting the photorealistic quality of the drawing itself, then it makes sense that even taking minute or two to draw something would be valuable. The key here, and throughout the rest of our time spent drawing, was to always be drawing; if we ever got stuck, we were to draw circles, or spell out the alphabet until we figured out what to draw next. To wit, here are my attempts at drawing Batman in one minute…

45 seconds…

25 seconds…

And finally, 15 seconds…

All quite scratchy, admittedly. The third one, in particular, looks to me more like a Batman-themed Christmas cookie gone horribly awry than the Caped Crusader, but the ears are recognizable, at least.

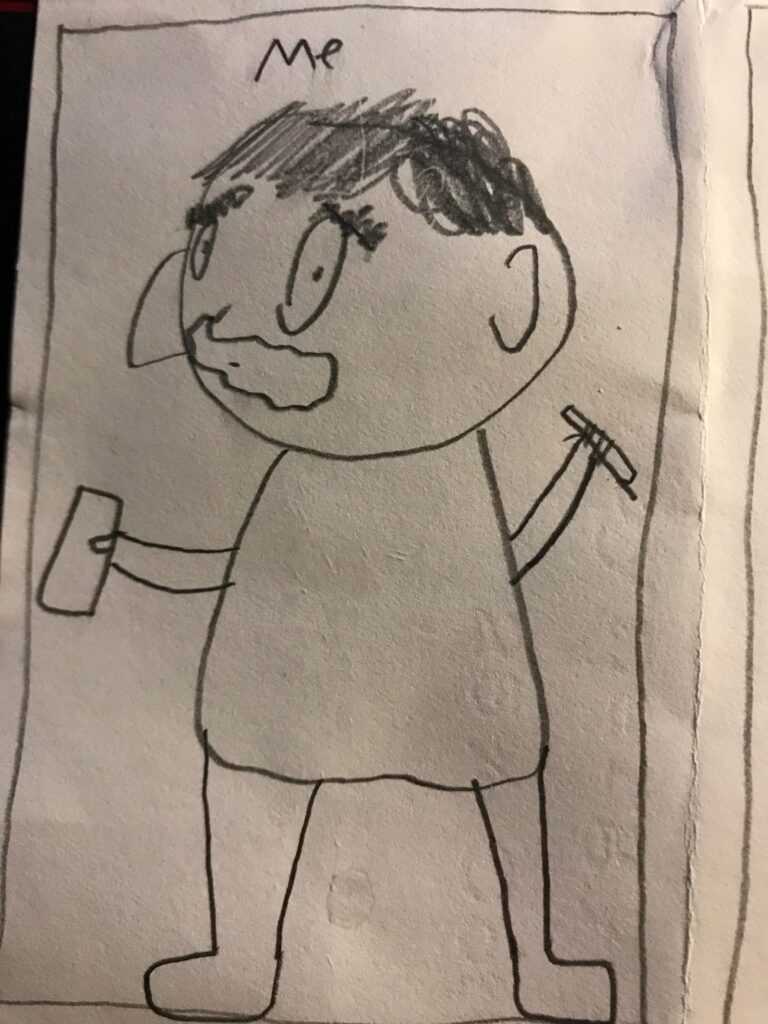

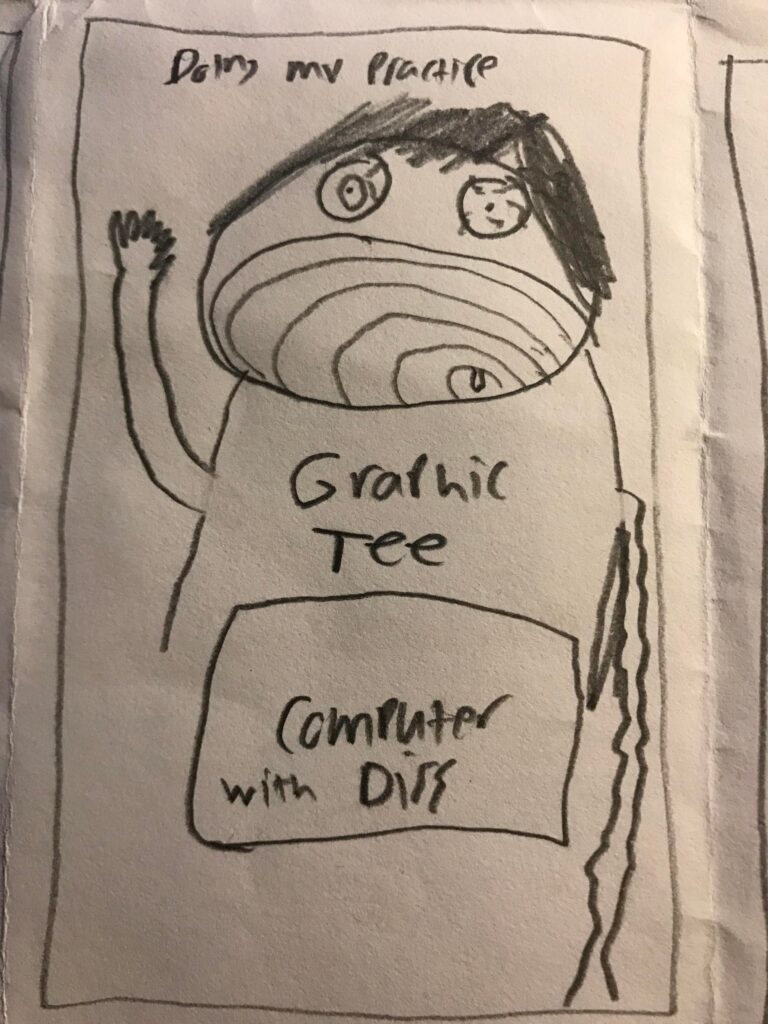

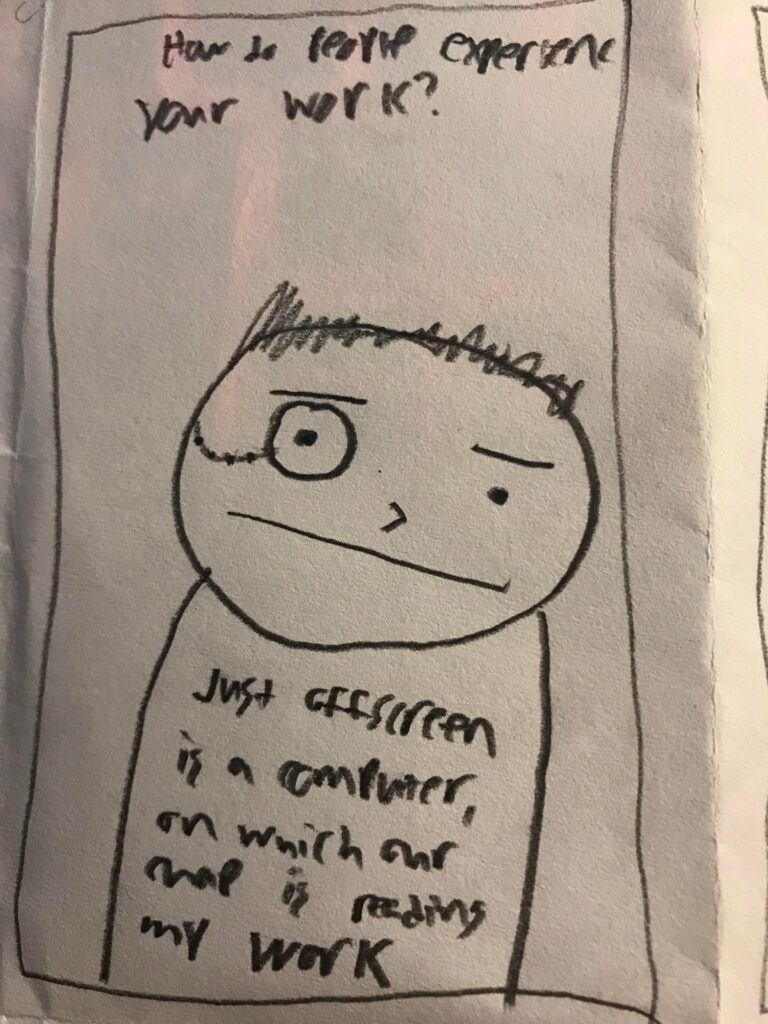

The next drawing project Liz assigned us was far more personal. Using notecards or a folded-up sheet of paper separated into eighths, we were tasked with drawing ourselves, our practice (whatever that term meant to us), what we study, and how others respond to, associate with, and are changed by our work, each in about a minute. Drawing myself was easy enough once Liz gave us some pointers. Simple shapes are best, with circles, gently rounded triangles, and more or less curved lines predominating.

My depiction of my practice, however, was far trickier. What to draw? What is my practice? Most importantly, what feeling do I wish to express in my drawing? So often my days are consumed by work on my dissertation, so depicting a typical writing session felt like the most obvious answer.

Looking back on this drawing, what strikes me is the manic energy I see. My mouth is open wide in a sort of performative scream, the eyes bloodshot, the hand raised in…what? Frustration? Despair? Anxiety? Or is it perhaps about to come down and strike my computer? It’s hard to tell; even now I cannot articulate in words the feeling that this drawing captures other than to say, “Yes, that looks right. That’s exactly it.” But what I appreciated about the environment Liz provided us that day was the opportunity to begin to work through my feelings regarding my own work. In the grind to write and achieve that graduate students are often enmeshed within, we don’t often get the time necessary to take stock regarding how we feel about our work. Drawing, it turned out, was a remarkably effective tool for doing just that.

I don’t know if I would say that I’m an artist again, but I do know that I loved to try to be one, in even the most amateur sense. Art opens up ways of communicating stories and meanings that words simply cannot have access to. The feel of pencil on paper is, itself, therapeutic. If nothing else, it gave me an opportunity to think about my work—and perhaps more importantly, mine and others relationship to my work—in new ways. It pays to take time to reframe, in this case in a very literal sense. So that said, thank you, Liz. I don’t think I’m going to add any of my drawings to my dissertation, but I’ve certainly been given a lot to think about.