By Director Anne Basting

In early September, Professor Jennifer Johung (C21’s Lead Faculty Advisor) and I met up on the 9th floor of Curtin to get the lay of the land at C21.

It was quite a trip.

Much of it hadn’t changed since I was first here in 1995. Then, over tea with Distinguished Professor Jane Gallop (C21 Advisory Council member), she told me “oh, it hasn’t changed since 1978.”

Jennifer and I thought – now’s the time to reimagine the (amazing) space of C21 – its views of the lake and downtown, its collaborative spaces, its spaces of contemplation and reflection.

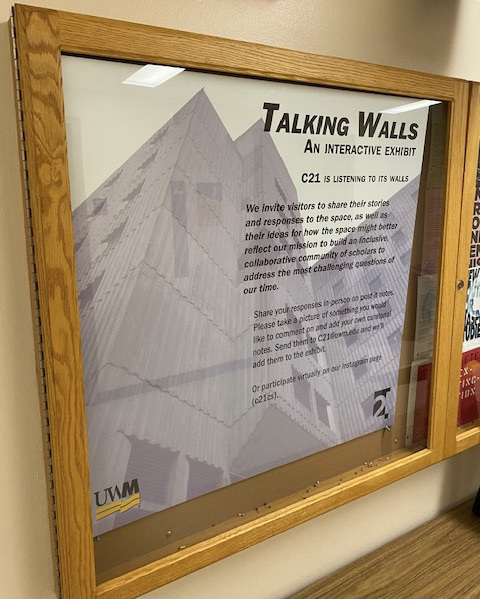

The first phase is Talking Walls, an interactive exhibit to invite people to share stories of C21 past, and visions of C21 future. With our mission to create a community of scholars to address the most pressing issues of our time, how might we best use our spaces – both physical and virtual?

Please find your way to Curtin Hall’s 9th floor and join us for the reimagining process. How could C21 better create a community of scholars – addressing the issues of our time? There are 19 curatorial cards that share history and pose questions. Please share your responses – here, on Instagram, or on post-it notes you can stick right on the wall in the actual space.

I owe credit for the title to Fellow (and former Advisory Council member) Christine Evans (History). As I explained my concept to her, she told me about how she had just read that in Russian military training, they had what they called “Talking Walls.” I leave you with her description here:

In the 1780s, a new director began to introduce Enlightenment ideas of education through self-cultivation to the Russian military’s leading educational institute, the Noble Cadet Corps. As historian Eugene Miakinkov explains, “the most creative part of the new director’s approach to education was the “talking wall” [“la muraille parlante”]. The walls of the garden were painted with astronomical drawings and moralistic expressions extracted from different books.” Throughout the week, moreover, “the cadets had to write their thoughts about what they had read on special blackboards.” One cadet remembered that “useful, even though superficial information of different kind[s] always struck one’s eye, so that even those pupils who were less disposed towards learning than others, unwittingly accumulated at least some knowledge.”–[from Miakinkov, War and Enlightenment in Russia: Military Culture in the Age of Catherine II, pp. 63-64]