by Molly McCourt (PhD Candidate in English, C21 Graduate Fellow)

My research focuses on social constructions of masculinity that have captivated the collective American imagination since the nation’s fraught beginnings. Through the lens of period pieces in 21stcentury television, I examine the myth of the self-made man and his pursuit of the elusive American Dream. While at times troubling, I argue that researching manhood and national identity elucidate why we watch these morally ambiguous men on screen and how industry, representation, and viewership encourage the social dominance of mostly straight, white, middle-class patriarchs.

Recently, my career goals have shifted toward activism and advocacy in a college setting. I hope to create equitable and empowering spaces for all students. Inspired by #MeToo creator Tarana Burke, I strive to encourage “empowerment through empathy” in my advocacy mission. I work to use my training in media, culture, and gender studies as a framework to challenge sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and abuses of power in academe. Considering the many hours of learning and teaching I have devoted to manhood in America, I must begin by confronting the person who literally wrote the book on it: Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies Michael Kimmel. In light of sexual misconduct charges brought against Kimmel, I find myself grappling with how to frame his scholarship within my own writing. This begs broader questions when considering how we can hold academics accountable in the #MeToo era: When a scholar you respect falls from grace, what do we do with their work? How do we reevaluate their contributions? Is there a way to include their work without bolstering their prestige?

In an article published in early August of 2018, the Chronicle of Higher Education exposed the sexual harassment allegations lodged against Kimmel by an anonymous former graduate student. On the cusp of accepting that year’s Jessie Bernard Award from the American Sociology Association, he deferred the award, requesting that his accusers come forward within the next six months so he can “make amends.”* Dr. Bethany M. Coston, a former graduate assistant to Kimmel, came forward a week later via Medium, detailing a litany of offenses they experienced during their time working under Kimmel. Included in the article are detailed accounts of Kimmel deadnaming transgender students, explicitly describing his son’s sex life in class, and privileging straight, cisgender male graduate students with professional development opportunities. As I read these repeated offenses of homophobia, transphobia, and gender discrimination, I felt anger and betrayal brewing inside, not only on behalf of these mistreated graduate students, but also for my own scholarship and devotion to his work. Kimmel has built his career debunking myths of stoic masculinity and challenging all men to recognize the benefits of feminism for men as well as women. So much of my understanding of the sociocultural history of manhood—in terms of national identity, race, class, parenthood, and politics—rests in the marginalia of his manuscripts. The more accounts I read—and believed—written by wronged graduate students, the less I wanted to cite Kimmel in my own work. As I began to grapple with this idea, I couldn’t help but revisit Kimmel’s talk at Marquette University two years ago in November 2016.

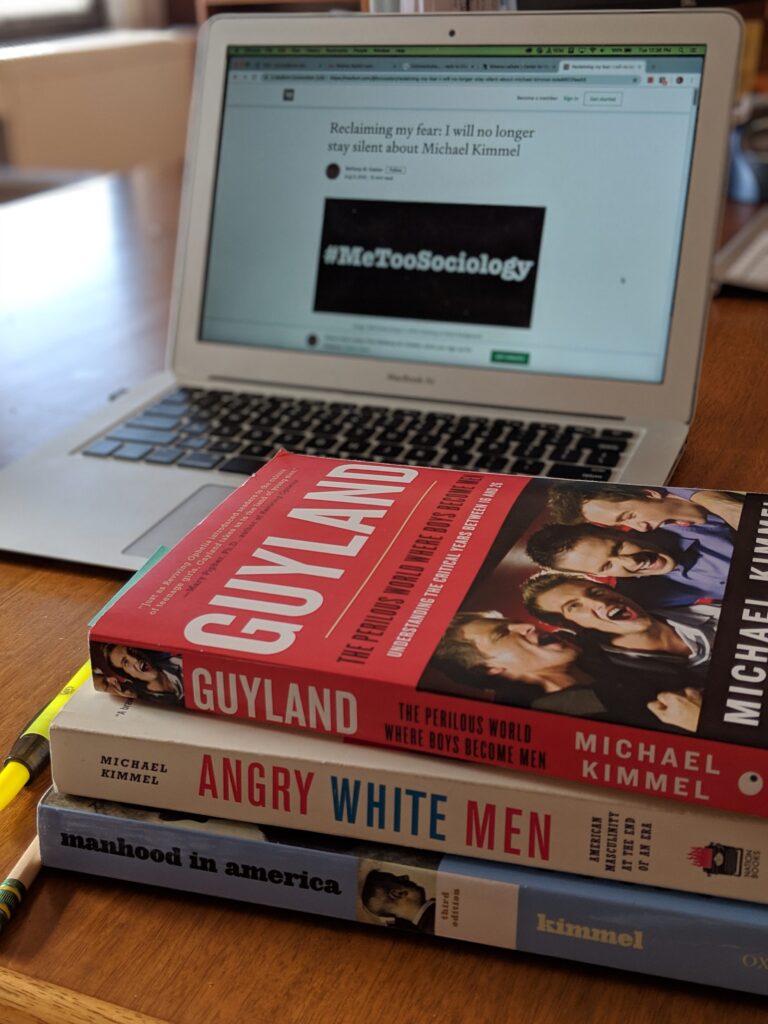

I remember eagerly waiting to see Kimmel’s talk. He was presenting material from his recently published book, Guyland, as part of Marquette’s Intersectionality Speaker Series. As part of my Film, TV, and Masculinity course at UWM, I had assigned specific chapters of this book to my class, as well as portions of Manhood in America and Angry White Men. My students found Kimmel’s writing interesting and accessible. In the lecture, Kimmel came off as sweet and smart. When it came time for the Q&A, my colleague Bridget Kies asked the first question. She first thanked Kimmel for his important work in the field of masculinity studies, and then politely pointed out that the bulk of his research is on straight, white men. “Can you talk a little more about how we might address people of color and individuals who identify as LGBTQ+?” Kimmel responded by saying he comes by his sociological approach honestly, and in order to understand the margins, one must first understand the center.

In the moment, it was validating to hear someone we respect defend the work we were also pursuing in media studies. In hindsight, however, I see this as a bit of a cop out. He didn’t address the obvious fact that he is a straight, white, cisgender man only studying others who identify as such. Kimmel also didn’t follow up in any way with a promise or hope to explore “the margins” in the future. There was no “and in my next project, I am going to travel the country interviewing people of color, gay men, and transgender folks.” He didn’t even name other scholars who were doing that kind of important ethnographic work. And in light of recent allegations, I now shudder to think that his rationale was more sinister than my colleague and I would have ever realized: it may be because he not only fails to understand individuals who identify as anything other than cisgender, straight, white men, but that he also doesn’t respect them. This is apparent when we examine feminist scholar Claire Potter’s tweets regarding Kimmel’s reputation for soliciting grad students for sex since the 1980s and Coston’s accounts of their faculty mentor’s inappropriate jokes that TUGs (transgender until graduation) are the new LUGs (lesbian until graduation).

While allegations of sexual misconduct are a difficult reality to face on an emotional level, they must also complicate the ways in which we think about citations. Invoking the foundational work of a senior scholar is expected of anyone engaging in critical academic inquiry. Failure to do so often results in strong suggestions from reviewers to revise and resubmit, along with either a clear instruction to cite a certain scholar, the implicit suggestion that one should cite them, and almost always, judgment for not doing so in the first place. Nikki Usher elucidates this conundrum in a Chronicle article by bringing to light an unfair binary too many academics face: “cite him, or you don’t know what you’re talking about to reviewers and readers.” In her case, she made the choice to avoid citing a sexist male professor, only to be reminded of a difficult truth after a “major revise and resubmit” request on her article: “If he is a predominant voice in your field or subfield, there is no way for you to avoid having to continue to build his academic reputation through citations.” Usher points out the added layer of complexity with professors that have no public allegations of sexual misconduct brought against them, even if their problematic behavior is widely known. In these cases, she writes that it is difficult to imagine a review board accepting a footnote explaining her intentional omission of the sexist scholar’s work. Usher’s article highlights the inextricable link between citation and career advancement, and the frustrations at the crux of this issue in the #MeToo era.

Bryan Leiter takes up the “academic ethics” of citation, asserting a different strategy for invoking scholars accused of sexual misconduct: cite them anyway. “Cite work that is relevant regardless of author’s misdeeds,” Leiter writes. “Otherwise, you are not doing scholarship, but something else.” Calling to mind not only recent allegations brought against John Searle, Avital Ronell, and Thomas Pogge, but also the well-known misdeeds of philosophers Gottlob Frege and Martin Heidegger (anti-Semitism and Nazism, respectively), Leiter claims that while we should condemn them, we should not excise these scholars from the canon. Doing so betrays one’s discipline as well as their academic freedom, according to Leiter. A comment following this article reads: “Finally an article separating the political from the academic! Scholarship must stand on its own merit.”

In a piece clearly devoted to the duty of the serious scholar, Leiter’s claim that we ignore the author’s misdeeds seems anathema to the charge of a true critical thinker. When learning the foundations of high level thinking, isn’t it our responsibility to consider the culture surrounding a text? Otherwise, we are taking the object of study in a vacuum, and thus denying ourselves the ability to understand it fully. A responsible researcher must understand the context of scholarship, which means we also need to understand the whole scholar. The idea that the political and academic realms are ever able to be separated reinforces this flawed logic. It is short-sighted, to say the least, to view scholarship of any kind as a mere “contribution of knowledge,” as Leiter writes. We bolster the legacy of these problematic scholars by citing them. This led me to wonder: How else can we prove that we are aware of their legacy and call them out simultaneously? How can we grapple with context and hold a scholar accountable especially when—in Michael Kimmel’s case as a self-proclaimed feminist accused of sexual harassment— their field and behavior occupy the same mental and physical space as their misconduct? Other creative fields have come up with their own forms of retribution against perpetrators of sexual misconduct. One example of this exists in the hardcore music scene’s call-out culture in which individuals who commit acts of sexual harassment are called out across all social media platforms and effectively excommunicated from the entire community. What would a collective response like this look like in academia?

One thing Leiter fails to explain is what exactly one does if they refuse to cite an author accused of sexual misconduct. He simply states, “you’re doing something else.” Could the “something else” Leiter speaks of be a new form of resistance? What if scholars that wanted to hold perpetrators of all forms of sexual harassment accountable by calling out other actors in a positive way? As a type of academic activism, I propose we dig deeply into the footnotes, indices, appendices and acknowledgments of those foundational manuscripts to cite the author’s research assistants. I realize it will be difficult to separate out the parts of the publication that are the graduate student’s contributions. But if we at could start by including their names in our citations, it allows us to createa new, more accurate and equitable reality—one in which Kimmel no longer stands alone as the sole architect of a certain idea. If we start remembering and reiterating that each scholarly publication reaches our eyes thanks to the efforts of multiple individuals as opposed to one, think about the implications this idea would have regarding the troubling power dynamics running rampant in academe. Of course, one still needs to train, test, defend in order to rise in the ranks; I am not suggesting we abolish this model of rigorous learning altogether. But what I am arguing is that we need to recognize power as the root of harassment. If we can begin to rethink the way we cite our research by crediting multiple minds and not just one, we might be able to prevent toxic hierarchy from taking hold in the first place. This also puts pressure on current and emerging scholars to name their assistants in a prominent way and make it easier for researchers to credit each name in between the parentheses. This practice may crowd the covers of future books and extend the length of a publication’s endnotes. I see this as a small price to pay for trying to affect change within an environment that has bolstered the legacies of sexual harassers and fostered an imbalance of academic power for far too long.

Later in the semester, I will present research that examines notions of masculinity, nostalgia, and the American Dream. These are concepts that many graduate students who once worked under Michael Kimmel researched thoroughly. So far, the names of Kimmel’s former assistants I have been able to gather are as follows: Bethany Coston, Randi Fischman, Charles Knight, and Grace Mattingly. I plan to keep uncovering these names and citing their research alongside Kimmel’s each time I draw upon any of his published material. By bringing other names into the canon and explaining the meaning behind it, I plan to call out Kimmel’s misconduct while also applauding his graduate students’ research efforts. While this is by no means a perfect solution, at least it is a form of active resistance. Scholars of all ranks must hold each other accountable. It is high time the culture of complicity surrounding sexual harassment in academe draws to a close.

—-

*This six month deferment period will be over this month. No word yet as to how the American Sociology Association and Kimmel plan to move forward.