By Richard Grusin (Director of the Center for 21st Century Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee)

Mid-way through the Trump presidency, it seems apparent that the greatest terrorist threat to American social and political order is not radical Islamism, cyber warfare, migrants, or climate change, but the threat of Trump’s tweets.

Mid-way through the Trump presidency, it seems apparent that the greatest terrorist threat to American social and political order is not radical Islamism, cyber warfare, migrants, or climate change, but the threat of Trump’s tweets.

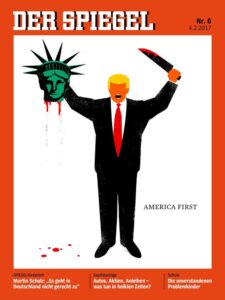

We often think about mediation and communication as separate from the acts of violence that circulate through media coverage, especially the recent failed mail-bomb attempts and the tragic murders in the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. There is another way, however, to understand the relation between mediation and terrorism. If terrorism works by creating and spreading fear, then it does not seem to be difficult to think of Trump’s tweets and other socially mediated acts of communication as forms of terrorism themselves, independent of the violent acts of terror which, as we have recently and tragically witnessed, he has incited. Trump’s incessant mediation is best understood as The Trump Show, a kind of “gesamtvermittlung,” or total mediation, which operates to captivate and terrify the American public into tolerating a level of criminal and immoral behavior that would have been totally unacceptable in any previous presidency.

In a recent collection of essays on Trump and the media, three different contributors take up the role of what I have called “premediation” in the election of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the United States. Zizi Papacharissi describes the way that news headlines help shaped Trump’s election by premediating his presidency in a variety of different ways. Keren Tenenboim-Weinblatt argues that journalistic premediations of Trump’s likely defeat by Hilary Clinton “may have contributed to the surprising outcome” (115). And Mike Ananny has argued that the media’s constant anticipation of Trump’s next move may have made his ultimate election inevitable. Arguments like these help to explain how the unthinkable election of Donald Trump came to pass. The media logic of premediation continues to govern US media in the second decade of the 21st century, and in fact helped to make the possibility of a “President Trump” seem plausible. But even though a Trump presidency had been premediated in innumerable news stories with headlines like “Trump’s First 100 Days” or “What Would a Trump White House Look Like?,” his election-night victory was nonetheless almost universally unexpected by transnational media publics and political pundits across the media spectrum.

One of the central premises of my Premediation book was that our interactions with media forms, practices, and technical platforms have a bodily, affective impact, related to but independent of the cognitive or representational content of these mediations. Through biotechnical feedback loops of anxiety, fear, and reassurance, media themselves generate affective responses similar to but different in intensity and sensation from those produced by unpredictable acts of violence like mass murder, explosions, or attacks on physical infrastructure. A recent example of this weaponization of Twitter was evident in a New York Times article about the Twitter trolling of Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi journalist murdered in Istanbul in October. As the Times article makes clear, this trolling had an affective, bodily impact on Khashoggi:

“Each morning, Jamal Khashoggi would check his phone to discover what fresh hell had been unleashed while he was sleeping. He would see the work of an army of Twitter trolls, ordered to attack him and other influential Saudis who had criticized the kingdom’s leaders. He sometimes took the attacks personally, so friends made a point of calling frequently to check on his mental state. ‘The mornings were the worst for him because he would wake up to the equivalent of sustained gunfire online,’ said Maggie Mitchell Salem, a friend of Mr. Khashoggi’s for more than 15 years.”

In talking about Twitter trolling as a form of attack, the Times and Khashoggi’s friends are not being metaphorical but asserting that there is no categorical separation between Twitter trolling and acts of violent assassination and dismemberment. Rather, these acts of violence are continuous insofar as Twitter is itself a form of mental/emotional violence that the Saudis employed as part of a coordinated attack on Khashoggi’s life. Trump’s tweets, too, I would argue, can be seen not as mediations of violence but as violent mediations themselves.

We have witnessed these terrorist tweets repeatedly over the past two years—in Trump’s threats of massive violence against North Korea’s Kim Jong Un or Iran’s Hassan Rouhani, or his threats to build a wall on the Mexican (or even Canadian) border, or to instruct troops sent to stop the “caravan” from invading America to consider rock-throwing by aspiring immigrants as a reason to be fired upon. Trump’s direct threats against refugees, other nations, and transnational alliances not only function to destabilize and unsettle political leaders worldwide but inflict collateral affective damage on the US media public. But it is the domestic terrorism of his incessant attacks on the US news media, his own justice department, Democrats, the court, the environment, women, trans individuals, and people of color that have transformed the Trump presidency and its incessant mediation into a pervasive, constant threat to the American public. On the very same everyday print, televisual, and socially networked media which Americans commonly use to track their sports teams or the weather, to share photos of family activities or birthday greetings, or to follow their favorite celebrities, news stories about or generated by Trump and his administration loom as everpresent threats, ready to disrupt the daily rituals, practices, and institutions of community and culture with destabilizing attacks from the nation’s ostensive leader, a position that has functioned historically as a source of national stability and reassurance. At the end of the second decade of the 21st century, Americans live and work under constant threat of presidential terrorism.

It is useful to think this terrorist mediation under the rubric of The Trump Show, a socially mediated political successor to Peter Weir’s satirical 1998 film The Truman Show. But where The Truman Show envisioned an entire life as total work of art, a reality show broadcast live on television to viewers around the globe, The Trump Show remediates television for the 21st century as total mediation, unfolding across every available format of print, televisual, and networked mediation. In an age of networked digital media, television, like cinema, is distributed across a variety of media forms and platforms. The plot of The Trump Show and its huge cast of characters plays out across all forms of media. Unlike The Apprentice or America’s Got Talent, there is no single regularly scheduled Trump show on a particular network. Like The Truman Show, The Trump Show can be seen 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, around the world on almost every media platform you can imagine.

Despite Trump’s strategy of Twitter trolling, he is hardly an evil genius controlling The Trump Show in the way that Christo, the fictional creator and producer of The Truman Show, controlled its every scene. Rather than the autonomous agent behind this total mediation, “Trump” himself is the product or outcome of an ever-growing assemblage of billions or trillions of everyday mediations. Trump is the sum of his tweets, the White House press releases, his formal and informal press conferences, his rallies, statements by his spokespeople, the leaks, bots, and social media sites. The name “Trump” itself is an iconic corporate brand on buildings and products and deals, as well as on the policies and official statements of the executive branch. These innumerable remediations of “Trump” are by no means all willed and intentional; they are the automatic technical products of platforms and practices and formats that reproduce “Trump” algorithmically. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, Trump’s evil mediation operates by occupying the total space of the media with their participation and cooperation. Despite portraying the media as the enemy of the people with whom he is at war, Trump’s strategy of total mediation works collaboratively with print, televisual, and networked media to radically mediate and remediate “Trump” as a political brand which is reproduced, circulated, and multiplied, realized virtually and actually by these countless streams and clusters of mediation and remediation.

Unless—or until—we acknowledge our own and the media’s agency in enabling Trump’s nomination, election, and continued imperious governance, we will be unable to get The Trump Show off the air. Nor am I convinced that the results of the midterm elections will have any efficacy in stopping it. The feckless Democrats are unlikely to have the conviction or power to impeach him; besides, anything they do to oppose Trump is likely to continue to make him stronger. While it is possible that a Democrat majority in the House of Representatives will allow them to slow down more tax cuts and tie Trump up in investigations into his finances, campaign violations, or obstructions of justice, Trump will certainly turn almost anything they do against them. A Democratic House in 2018 is likely only to increase Trump’s viewership, creating new national and international conflicts, new heroes and villains to battle against the GOP’s superhero.Because Democratic opposition will appear outrageous to those who love Trump or merely shrug their shoulders at his obscene behavior, he will do everything he can to transform that outrage into fodder for The Trump Show’s renewal in 2020.

As all good television watchers know, nothing gets a show canceled more quickly than if people stop watching and talking about it. Too much winning, as Trump promised in the 2016 campaign, can get boring. Perhaps then the best bet to get The Trump Show off the air is stop the constant fighting and obsessing, the outraged tweeting and meme-ing and Facebooking, the constant interviewing and opining. Perhaps we should let the Make America Great Again cultists grow complacent with their power while we focus on building truly progressive policies and programs, on creating candidates who can articulate winning and compelling visions that the American media public want to watch and follow as closely as they now do Trump.

Media attention is the wind in Trump’s sails, the hot air that keeps the Trump balloon inflated. Let’s blow up our own balloons and launch our own vessels into the future. The sooner this happens, the sooner we begin focusing on social and economic justice, on healthy environments and sound infrastructures, on education and culture and the arts, the sooner the Trump Show will reveal itself to be the hollow, pathetic, and corrupt production that it is. Continuing to mock and revile Trump’s every move only strengthens the resolve of his supporters, and keeps Trump in control of the multiple hypermedia channels that he now dominates daily. The sooner we can change the channel, the sooner the Trump Show will jump the shark, and the sooner the American public will see his presidency cancelled in favor of the next new political media property. But changing the channel is a more difficult challenge than ever before. While The Trump Show will at some point run its course, it is at this point way too early to have any clear sense of what kind of mediation will succeed it.