By Heather Warren-Crow

Let’s begin numerically.

Right after 9.11.01, envelopes containing Bacillus anthracis were mailed to 2 US senators, a news anchor, the editor of the New York Post, and the headquarters of the publisher of Playboy and The National Enquirer. At least 22 people contracted anthrax. 5 died. According to the Department of Justice, these attacks are believed to have been perpetrated by Dr. Bruce Ivins, a microbiologist at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (he wasn’t convicted, as he committed suicide before his indictment for the “Use of a Weapon of Mass Destruction, in violation of Title 18…Section 2322a”).[1] In the decade after this event, officially branded “Amerithrax,”[2] the US Government spent 60 billion dollars on biodefense, including the stockpiling of more than 28.75 million doses of the anthrax vaccine.[3]

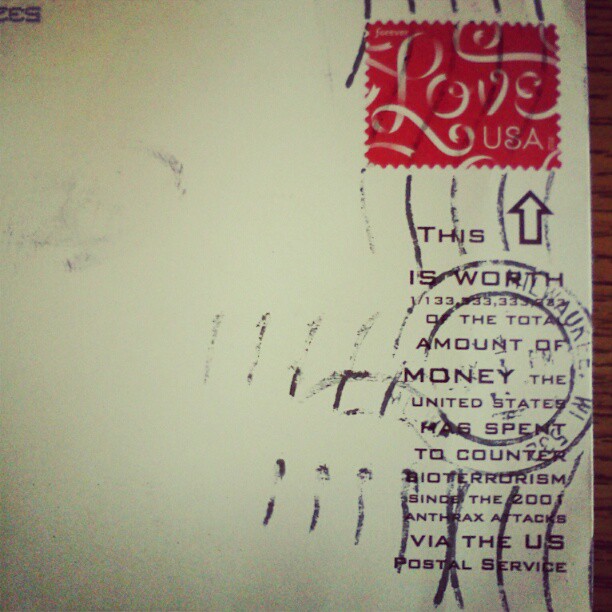

I encountered this information as part of my research for the exhibition The Tool at Hand Milwaukee Challenge. Local artists were asked to make an artwork using only one tool. My contribution was a performance in which I used my tongue as a tool to lick envelopes printed with the following statement, accompanied by an arrow pointing upwards toward the stamp: “This is worth 1/133,333,333,333 of the total amount of money the United States has spent to counter bioterrorism since the 2001 anthrax attacks via the US Postal Service.” After inviting visitors to write notes to people of their choosing, I sealed the envelopes and handed them back for participants to put in a mailbox or give to a carrier.

One of my intentions was to use the postal service as an alternate mode of circulating information at a time in which the Internet and television are Americans’ main sources of news. I wanted to draw attention not only to the facts of federal spending, but also to the materiality of communication—always operative but easy to ignore when it comes to networked media. Although a full explanation of the goals of my performance lies outside the scope of this post, I will say that the process drew attention to the discomfort many of us feel around mail, especially those who pay bills online or over the phone. One participant picked up a just-licked envelope by its corner, as if I had given him a used Kleenex for a birthday present.

Motivated by the uncanny materiality of things, this post is an opportunity for me to think about Amerithrax as an event with applicability to the Nonhuman Turn. What follows is more storytelling than analysis. Focusing on the “Amerithrax Investigative Summary” (AIS), I will re-orient this official explanation towards its nonhuman but nonetheless vital actants.[4] I don’t mean to minimize the human tragedy of the event or discredit the necessity of locating perpetrators. On the contrary, recognition of the imbrication of human and nonhuman life can provide a broader context for understanding criminal investigation, which is increasingly dependent on forensic science, as well as bioterrorism, which maximizes affective violence by hijacking preexisting assumptions regarding the supposed ontological and epistemological purity of the human. The Amerithrax letters exacerbated post-9/11 Islamophobic panic concerning the boundaries between Self and Other with a message praising Allah and directing the reader to take penicillin. Based on the exact phrasing and the highlighting of As and Ts (believed to stand for nucleic acids Adenine and Thymine), investigators quickly determined that the letters were the work of not a “true jihadi,” but a “home-grown attacker” (“home,” “growth”—two ideas I’ll return to later).[5]

Let me retell this story from its (arbitrary) beginning.

B. anthracis takes its name from the Greek word “anthrakis,” or, “coal,” a reference to the black lesions of the disease’s cutaneous expression. It’s remarkably resilient. When faced with an inhospitable environment, it forms spores to hide its genetic material inside three protective layers. They can remain alive for decades, waiting for a more propitious home. Although B. anthracis prefers to live within field-grazing animals, it will occupy humans, as well.[6] Historically, these victims were textile workers, giving the disease the old names Woolpickers’ and Ragsorters’ Disease.

About a hundred years after anthrax (and French livestock, a rabid dog, and a sick boy) helped make Pasteur famous, a strain of B. anthracis was isolated from the corpse of a 14-month old heifer in Sarita, Texas. All 5 people who died from anthrax in 2001 came in contact with a single-spore batch of what was originally extracted from this cow. Called RMR-1029, this particularly pure batch was maintained by Ivins, whose relationship with RMR-1029—somewhere between manager, owner, and caregiver—was instrumental in identifying him as the primary suspect.

Ivins had a powerful attachment to things. Obsessed with the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority, he was known to drive several hours to gaze upon different KKG sorority houses (the AIS implies that his fascination was with the buildings and not their denizens). Twice, he stole KKG “secret ritual material.”[7] He placed advertisements in magazines offering to send copies to all interested parties.

Various other textual objects played significant roles in the Amerithrax investigation. Let’s begin with the spores, themselves: RMR-1029 is from the famous Ames strain, misnamed after what was isolated from the cow in Texas was put in a box with a return address in Ames, Iowa. More important to the investigation were those paper goods that Ivins attempted to remove from circulation as well as those he sent on their way. Per the latter, Ivins was known to mail packages labeled with false return addresses, often placed in distant mailboxes. Per the former, the AIS finds great significance in a trash bag containing the article “The Linguistics of DNA” and Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, a book earnestly described as “difficult to summarize what [it] is about.”[8] More supportive of their case is the fact that all of the Anthrax letters were dropped in a mailbox across the street from a Princeton University KKG sorority office.

In the service of criminal investigation, forensics supports a notion of agency that’s exclusively human. However, even a dry government document summarizing such an investigation ascribes a surprising power to objects that approaches some kind of agency. Amerithrax brought together a number of powerful things—codes, cows, coal, lymph nodes, tongues, houses, bacteria that make bodies their homes, even the Thought Objects “home” and “growth.” Indeed, it weaponized these two Thought Objects as strategically as it turned envelopes into agents of circulatory destruction.

[1] United States Department of Justice, “Amerithrax Investigative Summary” (2010): 1, accessed May 11, 2012, http://www.justice.gov/amerithrax/docs/amx-investigative-summary.pdf

[2] “Amerithrax” is used to refer to the investigation and (retroactively) to the event, itself. I find the FBI’s decision to portmanteau the name of this country and the name of a bioweapon extraordinary.

[3] Erica Check Hayden, “The Price of Protection,” Nature 477 (September 8, 2011): 50.

[4] Since I’m not an investigative journalist, I’m not in a position to confirm or deny the accuracy of the report.

[5] US Dept. of Justice, 57.

[6] For an excellent overview of anthrax see Jean-Nicolas Tournier et al., “Anthrax, Toxins and Vaccines: A 125-year Journey Targeting Bacillus anthracis,” Expert Reviews and Anti-Infections Therapy 7:2 (2009): 219-236.

[7] US Dept. of Justice, 10.

[8] US Dept. of Justice, 61.

[Heather Warren-Crow is a scholar of media art, a performance artist, and a C21 Fellow. While at the Center she has worked on her book project, “Girlhood and the Plastic Image,” which intervenes equally in the fields of girl studies and digital culture studies, arguing that reproduction, dissemination, and consumption of plastic images are understood in connection to feminine adolescence. Her connection with the Center will continue – she is part of a group of scholars who were just awarded the Transdisciplinary Challenge Award for its research project, “21st Century Voices: Synthesized Speech in the Third Millennium”]